I’m continuing on my line of thought from my last post “On Reflection,” and have been considering how reflective practice and its counterpart of empathy can be taught in nursing school. How can we do a better job of helping students grow in emotional and moral maturity? How can we as health care providers and teachers do a better job of growing in our emotional and moral maturity?

Maura Spiegel who teaches in the Columbia University Narrative Medicine program gave a talk “Reconceptionalizing Empathy” last fall at the Narrative Medicine workshop I attended. She maintains that empathy cannot be taught, it can only be cultivated, and that a common mistake for health care providers in thinking about empathy is the idea that “I can know you—or that empathy can be a conduit into a patient’s inner life.” The psychoanalyst Donnel Stern maintains that empathy is an interpretation like any other observation, and that empathy is often implicit knowing or “pre-reflective unconscious, an unthought known:” a dimension of experience which is in some sense known, but not yet available to reflective thought or verbalization.”

Metaphor, poetry and art speak directly to our implicit knowing—they are, in Maura’s words, “mediated sources of understanding.” In health care, this is where narrative medicine and the medical humanities step in. Attentively watching movies, reading novels or poetry—or writing and reading our own stories—can tap into the sources of empathy. Language can become an ally again, and the experience of empathy can be made available for reflection. Making more room in nursing curricula for narrative medicine/nursing would be one way to help cultivate empathy in students—and perhaps even in faculty members.

Being able to access empathy and then to reflect on the experience are important skills for nurses. Certain patients or health care situations will affect us more than others. It is easier to have empathy for patients we assess as being “like us” in whatever aspects. Patients, groups or populations viewed as “the other,” are more difficult to have empathy for.

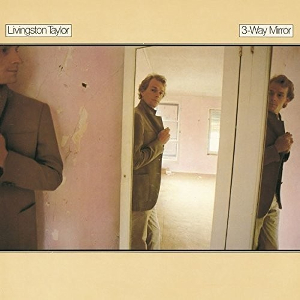

I recently read a collection of essays called The Other by Ryszard Kapuscinski (Verso, 2008). Over his long career as a journalist, he traveled throughout the developing world, reporting on major wars and revolutions. Kapuscinski was influenced in his thought by the philosopher Levinas, who is known for the phrase, “the self is only possible through the recognition of the Other.” Kapuscinski extends that thought by writing, “…the Other is a looking glass in which I see myself, and in which I am observed—it is a mirror that unmasks and exposes me, something we would prefer to avoid.”

Whenever we talk about “The Other” or “Othering” in nursing education, it is almost always in the context of working with patients and groups from “other cultures” or who have stigmatizing conditions such as schizophrenia. We don’t do a very good job at helping students to use their own inevitable discomfort in looking in that mirror to see what is reflected back, to see what is exposed. Sometimes these sorts of issues get handled by students in reflective journals in their clinical rotations, and sometimes it gets discussed in small group seminars—but those times are very few and almost seem to happen by accident. They aren’t explicitly cultivated. One of the problems that I see is that nursing faculty aren’t very comfortable in looking in the mirror themselves, so they aren’t able to model that for students. Encounter Groups for nursing faculty sound like a horror movie in the making, and continuing education conferences on how to cultivate empathy are close behind in the shudder index. One promising change may be that the next generation of nurse educators will be—well—younger, and perhaps more widely educated, more well-traveled, and further along on the emotional and moral maturity scale. That’s my hope.