Living on the West Coast of the US, I am aware of the maps showing the projected pathway of the nuclear fallout plumes swirling across the Pacific our way. For the record, I am not swilling iodine pills or wearing an equally ineffective paper mask. It does, however, put health care policy in perspective, and it makes me curious about public health messages.

The 1-2-3 catastrophic punches endured by the Japanese over the past week are difficult to avoid thinking about, no matter where you live. I am not Japanese, and have only set foot on Japanese soil (or anti-soil—it is an amazingly clean airport) in Narita airport many times changing planes on my way to Thailand. Part of my soul belongs in Japan, my mother having been conceived and born there, in the year of the great Tokyo earthquake.

The health consequences of what is happening in Japan are huge. It highlights—again—the interconnectedness of all countries of the world—the boundarylessness of germs and consequences of environmental degradation. But in a more concrete, less “we are the world” way, I think of the long-term health consequences of the nuclear fallout.

At one of the community health clinics I worked at, just north of Seattle, we had a large population of Ukrainian refugees. This was about 15 years after the Chernobyl accident, and many of our patients had been babies or small children living near Chernobyl. Many now had thyroid cancer, but many of their parents are more ill defined health issues, most likely the result of PTSD. Many of these patients were Pentecostal and had endured religious persecution in their homeland, combined with nuclear fallout, and sudden displacement from their homes and countries. Then they had the stigma of being ‘radioactive’ Chernobyl survivors. Compounding their trauma was the well-deserved deep distrust of government health messages, since they had been lied to about the extent of the problem around Chernobyl. Using a translator, I got to see these patients in 15-minute clinic visits, struggling to understand, much less address their health concerns. I had the sense to know that trying to establish trust was probably the most important intervention I could offer them, and I did this by mostly listening and not pushing tests or drugs on them. I discovered that our standard ‘talk therapy’ treatment for PTSD had no place in their worldview. They preferred bodywork like massage or chiropractic care for PTSD, and I had to get creative with their health insurance companies.

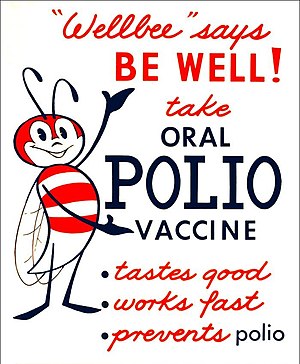

I learned a lot of cross-cultural nursing skills from working with the survivors of Chernobyl. I also grew in appreciation of our sometimes bungling but more transparent public health system in terms of disaster preparedness and public messaging. So with the Japan nuclear emergency, I checked in with our national and local public health official sites to see how they were handling this.

The CDC site is characteristically overburdened with links to various other national agencies involved in monitoring the current nuclear emergency. It has relatively clear information for US expats living in Japan in terms of health, safety and evacuation options. There’s a link to “Frequently Asked Questions About a Nuclear Blast,” which includes information on what to do when you are near the blast when it occurs: “Turn away and close and cover your eyes….” The CDC links to the Environmental Protection Agency for information of radiation, including “What is an atom?” and a really cute interactive virtual community full of radiation threats called “RadTown USA.” It includes information on radiation from the infamous airport body scan machines. Who knew that old Exit signs are a source of radiation in the environment? Overall, I would give the CDC site a ‘C’ in terms of health literacy for clear communication on this topic.

My local Seattle/King County Public Health Department does much better than the CDC on coverage of this issue. It states clearly “Nuclear event in Japan poses no health risk in King County,” and then backs up this assertion with quick and easy to read information. It advises the public against taking iodine pills, and most definitely against taking iodine water purification tablets as ‘prevention’ against radiation. Evidentially, our REI stores have had a run on them. The health department reminds us of the “3 days 3 ways” campaign for emergency preparedness, and there is a list of 17 natural and man-made disasters we should be prepared for in our area—these include civil disorder. We are an earthquake and tsunami-prone area with regular safety messages of “Drop, Cover, Hold!” in the event of an earthquake. The Washington State Emergency Management site adds: “Close your eyes, you’ll do better psychologically.” I think that one must be optional. Still, I’d give our local public health department an A- on health literacy. We tend to forget about the importance of consistent, reliable, and comprehensible public health messages, until we need them.